Download PDF: Joint NGO Reply to the Commission on the state of progress in implementing the CFP through the setting of fishing opportunities

On behalf of The Pew Charitable Trusts, Oceana, ClientEarth, Seas At Risk, FishSec and Our Fish, we present our response to the 2020 European Commission’s consultation on the progress of management of fish stocks in the EU.[1]

This year is unlike any other and the fishing industry has been heavily impacted by the COVID-19 crisis. We recognise the hardship many have faced and are still facing. We commend the Commission and member states for the development of emergency recovery plans to support industry through this difficult time. However, while Covid-19 response measures offer support in the short term, a sustainable marine environment supports livelihoods for years to come and the fishing industry will only be able to operate in the medium and long term if healthy fish populations thrive through sustainable harvest strategies.[2] This can only be achieved by setting total allowable catches (TACs) not exceeding scientific advice so as to recover and maintain stocks above levels that can produce the maximum sustainable yield (MSY), as legally required by the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP).

2020 is also an important year as it is the deadline to meet the CFP’s legal requirement of ending overfishing of all stocks. Although we acknowledge the progress made in reducing the number of overexploited stocks since the 2013 reform of the CFP, progress was too slow[3] and the deadline was missed.[4] Despite this missed deadline the EU must end overfishing of all stocks for 2021 without further delay.

The failure in meeting the 2020 deadline is not only a missed opportunity for a healthier marine environment. The Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY) objective was adopted by the EU in the 2013 CFP reform as an essential tool to improve the long-term economic and social benefits from fishing. Failing to rebuild fish populations and restore marine ecosystems prevents people enjoying the security and socio-economic benefits arising from long-term sustainable catches.[5] For the last seven years, NGOs have issued detailed analyses and recommendations regarding the Commission’s annual TAC proposals and the Council of Ministers’ meetings, specifically highlighting risks and issues in our responses to the Commission consultation on fishing opportunities – addressing the data and reporting shortfalls, and providing recommendations for more accurate and comprehensive TAC proposals. Unfortunately, most of the points raised in these various contributions have not been addressed and remain valid (see our joint-NGO response to the Consultation from last year).

This year should be different. President von der Leyen’s European Commission has committed to the European Green Deal[6] in order to overcome the threat that climate change and environmental degradation pose to Europe and the world.[7] For the Green Deal and the EU Biodiversity Strategy to succeed, overfishing must definitively end, as fishing is the key driver of ocean biodiversity loss at sea.[8] Ending overfishing is a concrete action, which will contribute to restoring fish populations and marine ecosystems. With more fish in the sea, fishers will need less effort to catch the same amount of fish so they will reduce their impacts on sensitive habitats and species, in addition to decreasing CO2 emissions. Ending overfishing will create healthier, more resilient ecosystems and coastal communities.

In this year’s response to the consultation, we would like to raise four CFP implementation gaps that should be addressed by the Commission to ensure that all TACs proposed and set for 2021 (and for 2022 in the case of deep-sea stocks) meet the objectives of the CFP, and the ambition of the European Green Deal.

I. Too little progress in implementing the CFP through the setting of fishing opportunities

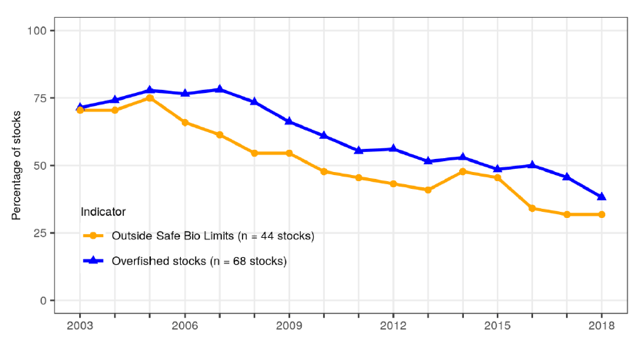

According to the 2020 CFP monitoring report of the Scientific, Technical and Economic Committee on Fisheries (STECF), around 38 percent of analysed stocks in the Northeast Atlantic (26 of 68) remain overfished in relation to the MSY exploitation rate. This is a decrease from 53 percent (36 of 68) in 2014 (Figure 1), a net reduction of 10 overfished stocks since the entry into force of the revised CFP in 2014.[9]

Figure 1 – Trends in stock status in the Northeast Atlantic 2003-2018. Two indicators are presented: blue line: the proportion of overexploited stocks (F>FMSY) within the sampling frame (62 to 68 stocks fully assessed, depending on year) and orange line: the proportion of stocks outside safe biological limits (F>Fpa or B<Bpa) (out of a total of 44 stocks). Source: Modified from STECF (2020). Red line: CFP entry into force: 1 January 2014.

Last year, the STECF emphasised that “many stocks remain overfished and/or outside safe biological limits, and that progress achieved until 2017 seems too slow to ensure that all stocks will be rebuilt and managed according to FMSY by 2020”.[10] This statement remains valid for 2020 (Figure 1) and contrasts with the more optimistic assessment of progress in the Commission communication, which seems to be based on different assumptions and metrics not included in the CFP. Indeed, the Commission now puts an emphasis on reporting in terms of landing volumes and median fishing mortality, instead of focusing on the number of stocks in line with the fishing mortality and biomass objectives of the CFP. This does not adequately reflect the CFP’s legal requirements, which apply to all stocks regardless of landings volume, commercial importance or data availability. It also distorts the picture by overly representing large pelagic stocks. Furthermore, it fails to acknowledge that several stocks (like cod in the Baltic and North seas, West of Scotland and the Celtic Sea) are outside safe biological limits and therefore only account for low levels of landings because they have been heavily depleted by overfishing and/or continue to be illegally discarded.

II. Failure to manage data-limited stocks in line with CFP requirements

Whilst many stocks in EU waters have suitable scientific information on the MSY exploitation rate and MSY-based scientific advice on catches, many stocks still only have scientific advice on catches based on the ICES data-limited precautionary approach. However, both of these stock categories fall under the scope of the CFP, which states that all harvested species should be restored and maintained above biomass levels capable of producing the MSY (CFP Article 2.2).

We note that the status of the data-limited stocks is, once again, omitted from this year’s Commission communication, which this time does not outline the approach the Commission intends to take when proposing TACs for these stocks. This is regrettable given that the Commission annually asks ICES for the best available scientific advice on catches of these stocks, which is comprehensively produced and delivered at significant expense to EU taxpayers. This omission from the communication risks reinforcing a two-tier policy approach, with less ambitious Commission proposals for stocks that are subject to ICES data-limited precautionary approach advice than for those that are subject to MSY-based advice. For example, in the Commission proposal for 2020 Northeast Atlantic TACs, 24 out of the 68 proposed TACs (35%) exceeded scientific advice based on ICES precautionary approach for data-limited stocks, while only 8 of the 68 proposed TACs (12%) exceeded scientific advice in relation to the ICES MSY approach or an agreed management plan (e.g. EU multi-annual plans) using the FMSY point value.[11]

This lower ambition for data-limited stocks is inconsistent with the precautionary approach as defined in the United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement (UNFSA) and in the CFP (Article 4.1(8)), which requires that when the available data and information are uncertain, unreliable or inadequate, decision makers should not postpone or fail to take appropriate conservation and management measures. Furthermore, it ignores that many of these stocks would, if they were given the opportunity to recover, support productive fisheries. While many of these stocks are relatively small in size or have lower economic value, they remain essential components of the marine ecosystem, and their harvest must therefore be adequately managed in line with implementing the ecosystem-based approach to fisheries management as required by Article 2.3 of the CFP basic regulation.

The ICES data-limited precautionary approach provides a framework for advice rules to set catches and manage the risk of overfishing stocks in a prudent manner, based on the levels of uncertainty in the available data. Not following the ICES precautionary advice for data-limited stocks goes against the precautionary approach and also against a key principle of good governance stated in the CFP, namely the establishment of measures, including the setting of catch limits, in accordance with the best available scientific advice (CFP Article 3.c).

Narrowing down the scope of official reporting by the Commission to MSY-assessed stocks only does not represent an adequate account of the overall situation of fish stocks, and the proportion of stocks which cannot yet be assessed in relation with the MSY should be explicitly recognised rather than being removed from the statistics.

III. Acknowledging that setting fishing limits is the most direct tool to improve fish stocks

The Commission highlights in its communication the efforts made in 2019 to adopt remedial measures under the MAPs to allow certain fish stocks to recover, like Celtic Sea cod and whiting and eastern Baltic cod. We welcome these efforts and indeed the EU was legally obliged to adopt remedial measures as safeguards under Article 8 of the Western Waters Multi-Annual Plan (WWMAP), to help rebuild Celtic Sea cod and whiting, and under Article 5 of the Baltic Sea MAP for eastern Baltic cod, since these stocks had fallen below Blim.

We commend the Commission for its role in securing these important measures. Nevertheless, we would like to highlight that the current very low biomass of these stocks is the result of a long-term trend of overfishing based on Council decisions that exceed advised fishing limits. For example, since 2014, the TAC for cod in the Celtic Sea has been set in excess of scientific advice every year except 2018.[12] Similarly, bycatch TACs have continued to be adopted for a number of other stocks with zero-catch advice, despite member states not having adopted the bycatch reduction plans and fully documented fisheries they committed to in December 2018.[13] The added pressure of other environmental factors on these vulnerable stocks in no way diminishes the role overfishing has played in depleting these stocks, and makes the adoption of effective recovery measures all the more urgent.

In that context, the Commission should reinforce through its proposals that the setting of fishing limits is the main tool available to rebuild and maintain the biomass of fish populations (as reflected in CFP Article 2.2). ‘Last hope’ remedial measures, while necessary due to past overfishing in some cases, are not the solution to achieve that objective, particularly if they are adopted only for some of the stocks in need, and while perpetuating the decades-long trend of setting TACs exceeding scientific advice.

If measures other than fishing limits are to be introduced, these must be coupled with legally binding, reliable and robust methods of full catch documentation, such as on-board observers or remote electronic monitoring (REM), in order to have a proper understanding of the fishing activity. This should be a high priority in particular for the vessels that have exemptions from the landing obligation (LO).

IV. Lack of implementation of the landing obligation

We remain concerned about the Commission’s continued support for various approaches to address the challenges of the LO (such as the setting of TACs based on catch advice, LO exemptions and bycatch TACs) despite the clear recognition by the Commission itself that compliance remains poor.[14] Continuing to apply such approaches based on the assumption of full compliance, whilst acknowledging unreported discarding continues, is incongruous and jeopardises the achievement of the CFP’s objectives.

Article 16.2 of the CFP basic regulation states that “fishing opportunities shall be fixed taking into account the change from fixing fishing opportunities that reflect landings to fixing fishing opportunities that reflect catches”. Article 16.2 does not however specify how the fishing opportunities should be adjusted, and it does not prevent the Commission from proposing TACs lower than the ICES catch advice, as it has done in a number of cases.

In order to accurately ‘reflect catches’ while following scientific advice, TACs need to be set in a way that ensures that the actual catches (including official landings, legal exemption discards and unreported illegal discards) do not exceed the ICES catch advice. Importantly, ICES catch advice is not advice for the level at which the TAC should be set, but advice for the maximum catch level not to be exceeded. Given the Commission’s repeated recognition that non-compliance remains widespread and ‘significant undocumented discards’[15] continue, it is clear that setting TACs at the catch advice level would result in higher than advised catches and in the end lead to overfishing.

In addition, the significant increase in the adoption of LO exemptions and bycatch TACs, particularly in 2019 and 2020, based on unclear scientific evidence and data,[16] further undermines the objective of the LO to reduce unwanted catch. The use of these approaches to ease in the LO, while robust and effective monitoring, control and enforcement are lacking, has only increased the risk of overfishing stocks in already poor shape and undermines the very basis of the CFP. We therefore strongly support the Commission’s push for the introduction of reliable monitoring, including REM, and highlight that until effective control mechanisms are in place, TAC-setting must reflect that unreported discarding continues despite the LO.

[1] EU Commission (2020), Towards more sustainable fishing in the EU: state of play and orientations for 2021

[2] For NGO recommendations please see: Setting the right safety net: A framework for fisheries support policies in response to COVID-19

[3] STECF (2019) – Monitoring the Performance of the Common Fisheries Policy

[4] See Pew Charitable Trusts analyses of Fisheries Council agreements on fishing opportunities for deep-sea stocks (2019-2020); Baltic sea stocks (2020); and Northeast Atlantic stocks (2020)

[5] Oceana (2017) – Healthy Fisheries are good for business, and Guillen et al (2016), Sustainability now or later? Estimating the benefits of pathways to maximum sustainable yield for EU Northeast Atlantic fisheries

[6] The European Green Deal Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, The Council, the European Economic and Social Committee of the Regions. The European Green Deal

[7] https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en, viewed 25 June 2020

[8] IPBES (2019): Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. E. S. Brondizio, J. Settele, S. Díaz, and H. T. Ngo

[9] STECF (2020) – Monitoring the Performance of the Common Fisheries Policy

[10] STECF (2019) – Monitoring the Performance of the Common Fisheries Policy

[11] Pew Charitable Trusts (2020) – Analysis of Fisheries Council agreement on fishing opportunities in the Northeast Atlantic for 2020

[12] http://ices.dk/sites/pub/Publication%20Reports/Advice/2019/2019/cod.27.7e-k.pdf

[13] Statement of the North Western Waters regional group made at December Council 2018, p. 2. Moreover, regarding the bycatch TACs, Recital 8 of the TAC and Quota Regulation for 2019 (Council Regulation (EU) 2019/124) stated that ‘all vessels benefitting from these specific TACs should implement full catch documentation as from 2019’.

[14] COM(2020) 248 Final. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council. Towards more sustainable fishing in the EU: state of play and orientations for 2021

[15] Ibid., p. 5.

[16] STECF (2019). Evaluation of Landing Obligation Joint Recommendations (STECF-19-08)