First published on Euronews, 2 December 2019: Depleted fish stocks can’t wait. The EU and Norway need to commit to ending overfishing now

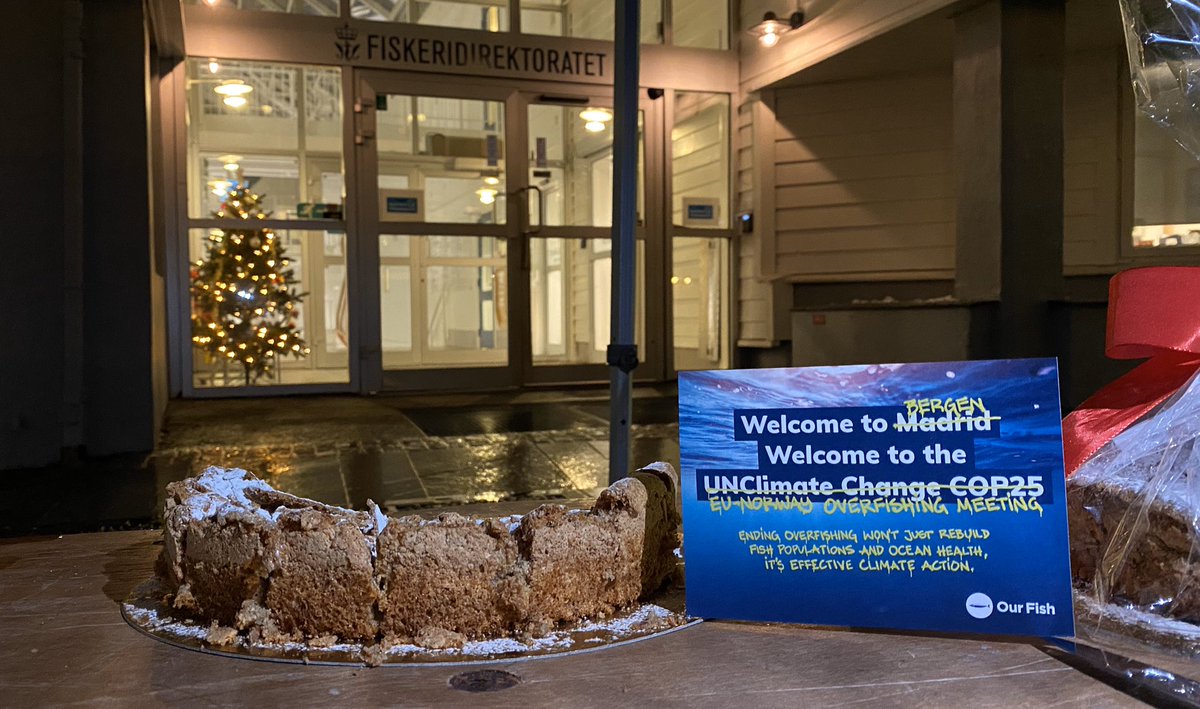

This week, in a quiet street in the Norwegian harbour town of Bergen, officials from EU member states and Norway will hole up in the Fiskeridirektoratet, or Fisheries Directorate, to decide the size of the fish pie to get divided out between them from so-called “shared stocks.” This “consultation,” as it is known, happens away from public scrutiny. Yet, fishing industry lobbyists are allowed in where they get to cosy up to delegates, while civil society representatives are – quite literally – left out in the cold. These annual gatherings are even more secretive than the EU AGRIFISH council meetings, which were recently investigated by the EU Ombudsman and found to be lacking in transparency.

EU-Norway consultations consistently result in agreements to continue overfishing. This is in no small part due to a bewilderingly flawed approach: by assuming the scientific advice for maximum sustainable catches as a starting point and then negotiating upwards. The EU committed to phase out overfishing under the reformed Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) by 2015 or, at the absolute latest, by 2020. Yet while the act of catching too many fish occurs at sea, it is inside meetings like this where overfishing is shamelessly agreed upon and approved.

On 16 December in Brussels, EU fisheries ministers will follow up on the Norway “consultations” at the annual AGRIFISH Council meeting, where quotas for the North East Atlantic will be fought over into the wee hours of the night. According to all the signs, this year they will again agree to overfish several key stocks.

The signals? Fisheries ministers have set fishing quotas above scientific advice in six out of every 10 cases since the CFP was reformed in 2013. The AGRIFISH Council very rarely sets fishing quotas at more sustainable levels than the EU Commission proposes. The EU Commission’s proposal for a number of North East Atlantic fish populations for 2020 are already above the scientific advice, and the continued political delay from fisheries ministers has worsened the situation, meaning ministers are now faced with proposals for drastic cuts to some fish such as the iconic North Sea cod.

Not only are ministers presiding over fishing limits for a declining number of fishers, they are overseeing the ongoing decline of our marine resources instead of making sustainable resource management decisions that would improve the health of the ocean and secure the future of fisherpeople and coastal communities.

The recent ground-breaking IPBES Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services estimated humanity is threatening a million species with extinction. It also concluded that the biggest threats to nature are from changes to land/sea use and over-exploitation. Overfishing remains the biggest impact on our ocean.

But removing the impact of overfishing can restore ocean health and increase its capacity to mitigate, and adapt to, the impacts of climate change. It is therefore a key form of climate action. This has started to permeate into policy. On 19 November, the EU Council, in response to the recent IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere, appealed to the EU Commission for policy options in the new Green Deal, while stating the need for urgent action to address the increasing threat of climate breakdown to the ocean and marine life.

So, missing the deadline of 2020 puts the EU in difficult territory. It places EU fisheries ministers in direct contravention of the laws that they, or their predecessors, created and signed up to, and in potential conflict with the climate action taken by other ministries within their own governments.

Norway, too, has invested a great deal in projecting itself as a climate and anti-overfishing champion, when in actual fact, it too, is hypocritical on both issues. On climate, Norway has made big commitments to become a ‘low-carbon society’ but in reality, emissions are decreasing much slower. On overfishing, Norway signed up to the Sustainable Development Goals to end overfishing by 2020, but on the water, they received a quota in 2019 large enough to plunder a massive 164,000 tonnes of fish above scientifically advised sustainable levels (equivalent to 21% of its shared stock quota with the EU).

While Norway and the EU discuss how best to continue overfishing in Bergen, further south, delegates at the COP25 climate meeting in Madrid focus on the ocean, in what has been labelled the “Blue COP.” With states under pressure to step up their commitments to action on climate, discussions will be focusing on why there is not more action on oceans when we know what needs to be done. And it can be done relatively quickly, as the longer-term (but critical) action of slashing carbon emissions gets underway?

Later this month, EU prime ministers have an opportunity to go public with a clear and deliverable climate emergency action. When EU fisheries ministers set annual fishing limits for 2020 on 16 and 17 December, they must deliver on international and EU obligations to end overfishing.

- Rebecca Hubbard is the Programme Director at Our Fish.